Rote and Demoralizing: Reading about Early WWII

I try to grapple with why I find the chapters about WWII harder to read than the earlier chapters about the rise of the Nazis.

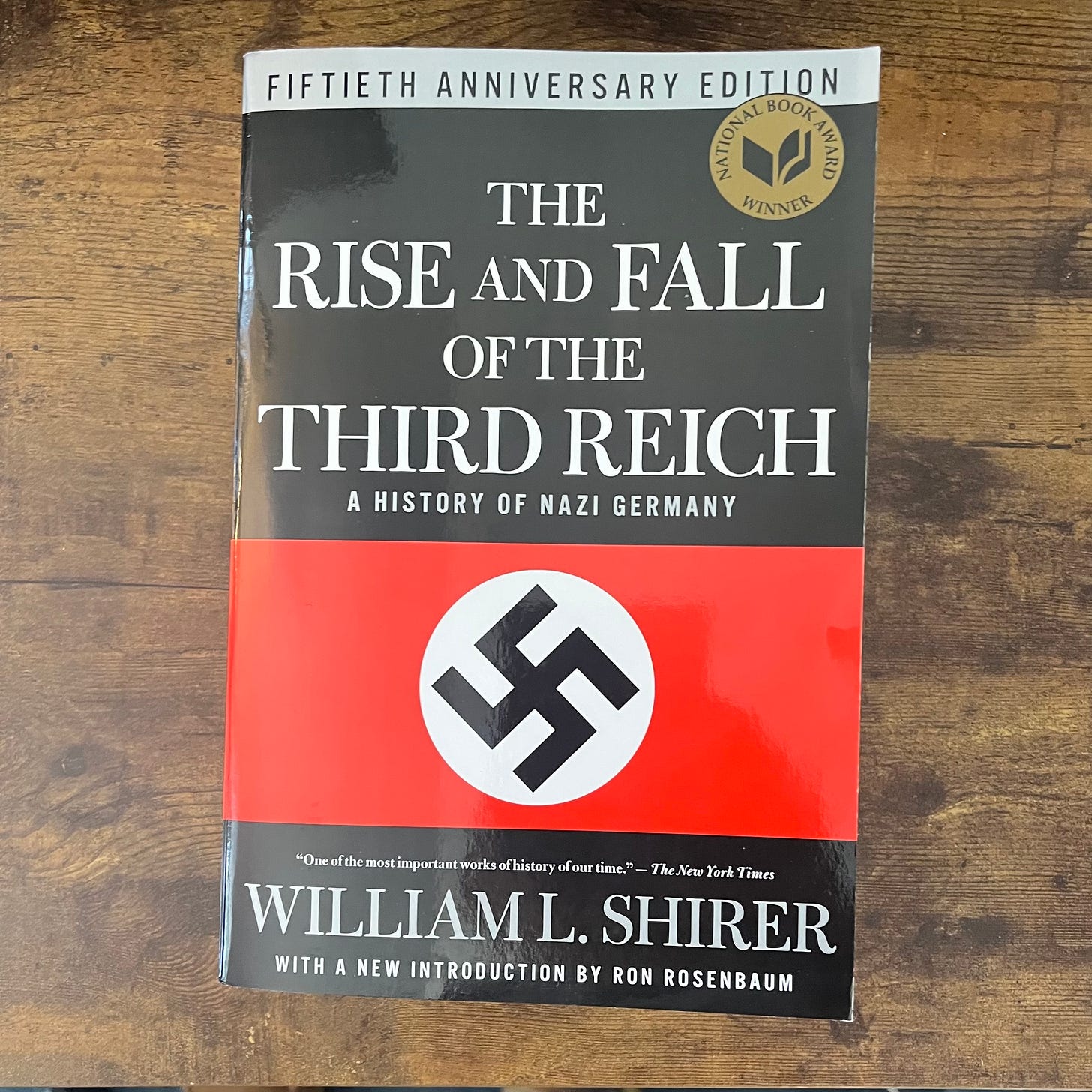

In reading these last few chapters in Shirer’s tome, I can’t help but notice that I feel very differently about them than I do the first half of the book.

The first half of the book is about the pre-history of World War II: the rise of Hitler and the Nazis.

These recent chapters are about Nazi foreign policy and the beginning of World War II. And I find them somehow overly rote and demoralizing. They even end up feeling repetitive. Austria falls. The Sudetenland falls. Bohemia and Moravia fall. Poland falls. Denmark falls. Norway falls…

You get the picture. Hitler sets his sights on one country and then, one after another, they all succumb. He says he wants peace but behind the scenes (or to anyone really paying attention), he clearly doesn’t. The leaders in each country are woefully unprepared to face him, diplomatically or militarily.

It’s all so… depressing.

The next chapter is about France—a country I care a great deal about. There, it will be more of the same. (Spoiler alert: France falls too.)

Now admittedly, after France, things do begin to change. The UK resists in the Battle of Britain, Hitler overextends himself by invading the Soviet Union, and the United States eventually gets involved, sealing Hitler’s fate.

Even without reading all of Shirer’s book, that is the part of the story we all know best. Then, I guess it does become more invigorating. The good guys win. The whole world doesn’t become Nazi.

In the meantime, though, I am having a harder time getting through these chapters to the denouement of the story.

And so I started wondering: why do these chapters read so differently to me?

I tried to remember back to January, when I read the first few chapters. What exactly did it feel like back then? What got me going?

There was a certain excitement in uncovering the Nazi backstory. I really wanted to piece things together. Since my entire life, I have had many pieces of the puzzle, just not always connected.

The Nazis are absolutely central to American culture.

In a negative way, to be sure. But they are central to America’s conception of itself. Adolf Hitler is the epitome of evil, his name the absolute insult. In their antisemitism, the Nazis represent the exact opposite of American liberal tolerance. In their book-burning, a denial of the core American values of freedom of inquiry and freedom of speech. In their land grabs, the opposite of the American form of hegemony, which largely renounces territorial annexation (at least in the key cases of WWI and WWII).

Our cacophonous media sphere, for all its faults, stands in contrast to the Goebbels-directed propaganda in Nazi Germany. And our electoral system, for all its fault, still churns on, allowing elections and new leaders whereas Nazi Germany froze the Weimar constitution and abrogated absolute power to one leader for life.

Those with a more nuanced view of the history—usually on the left—will quibble with the starkness of every one of these distinctions. But the fact remains that they’re mostly true and, more importantly, almost all Americans see themselves in this way.

So for me, when I read those first few chapters, there was a lively questioning that accompanied the reading: How did this happen? Could it have happened otherwise? If we do call into question the black-and-white distinction between the Nazis and Americans today, how similar are we in fact to Germans of the interwar period?

And then when the war started, that line of questioning stopped rather abruptly.

Before we got to it, World War II felt contingent. Maybe it wouldn’t happen. Maybe it could not have happened? At least, that’s what I entertained in reading about the 1920s and early 1930s.

Once the war started, though, that feeling dissipated. Of course, World War II has to play its course. Of course, one country after another will fall. Of course, there will be a turning point and the tide will shift. Of course, the Nazis will eventually be defeated.

I suppose some will read these chapters and try to glean some lessons about how democracies should be better prepared to resist authoritarian aggression. Personally, though I just don’t feel that line of questioning nearly as strongly as I did the earlier one. The seeds were planted in the earlier period. By 1938 and 1939 and 1940, it just seems too late to even entertain those kinds of questions.

At least that’s why I think I have a harder time getting into these middle chapters.

Maybe it is also that I am not a hard core military historian or even a typical History Dad. Understanding the exact details of how the Wehrmacht overpowered the opposition in each country is interesting to many. But that isn’t me.

How about you?

Do you feel a shift in how you read the book now that the war has actually started?

Topical Posts

Podcast ep. 1: The Man, The Myth: Hitler in American Culture

The Problems with the German Character Explanation of the Nazis

Podcast ep. 2: Why are Dictators (and Techno-monarchs) Appealing?

Podcast ep. 3: Interview with a 20th Century War Correspondent: Jon Randal

If You’ve Fallen Behind on the Reading, This Post is For You

Who was William L. Shirer? — part 2 (The Nightmare Years 1934-1940)

Podcast ep. 4: The Exhilaration & Peril of Covering the Nazis (with Prof. Michael Socolow) (Video, Audio)

Podcast ep. 5: What American Reporters Saw That Others Didn't (with Prof. Deborah Cohen) (Video, Audio)

Is this a historian / journalist split? As each country falls it’s a journalistic story, and I get caught up in them. One personal aside. James Gordon Bennet Jr., founder of the paper in Paris that came to be known as the International Herald Tribune (late and lamented), instructed his editors: “Names, names, names. News, news, news.” It’s a lesson that Shirer evidently took to heart.