Chapter 14: The Turn of Poland

Hitler's dishonesty becomes increasingly clear to all and war approaches in 1939

To begin this chapter recap, I wanted to highlight an idiosyncracy in the way Shirer names his chapters. This chapter is entitled “The Turn of Poland.”

To be quite frank, it seems a bit flippant. “Ok, Poland, now it’s your turn to be raped by the Nazis!”

Incidentally, the word “rape” seems to be a popular word choice in chapter titles about the Nazis. Here in Shirer, it is the “Rape of Austria” but “Czechoslovakia Ceases to Exist,” whereas in Evans’ book, it is the “Rape of Czechoslovakia.” The word “rape” somehow seems more fitting.

This chapter is one of five in Shirer that has some variation of the word “turn” in it. There is the “Turn of Russia”, the “Turn of the Tide” when the Third Reich first encounters real resistance from Russia, the “Turn of the United States” when it enters the war, and then the “Great Turning Point” about 1942 and Stalingrad.

That’s a lot of “turns.”

Of course, not all of these can be parsed as “it’s your turn to be overrun by the Nazis.” There’s a different sense of the word captured here—the sense in which one’s stomach turns or milk turns bad. “Turn” in the sense of a fundamental shift.

So the course of the war turns in Nazi Germany’s battle with the Soviet Union or the United States turns—or shifts—its geopolitical stance in World War II from neutrality to active engagement. In those cases, unlike for the early victims of Hitler’s foreign policy, there is some agency.

Here, though, there is no agency whatsoever for the Poles. Their country was turned. It was their turn to confront Hitler’s wild-eyed German nationalism and dishonest diplomacy. There is also an additional sense more closely related to turncoat or the way a spy is turned—a fundamental shift with a good dose of betrayal mixed in there.

In hindsight, it seems so obviously not the case, but to many contemporary observers (and actors in these events), the Munich Agreement in September 1938 really seemed to be the last concession necessary for German nationalism.

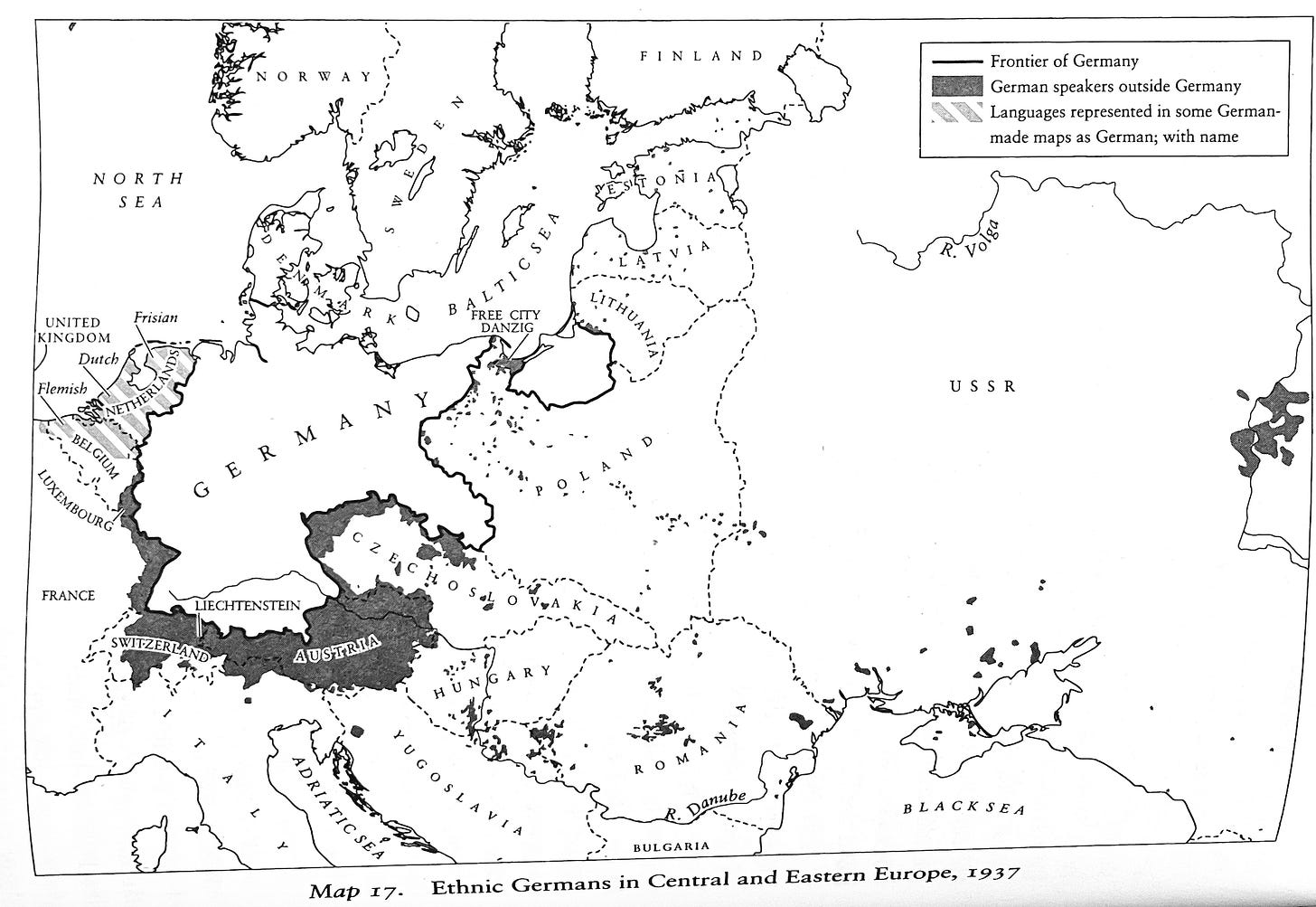

I return once again to this map of Germans outside Nazi Germany borders:

You can see that with the unification of Austria and the Sudetenland (in Czechoslovakia) to Germany, most ethnic Germans in Europe were then part of the same country.

What Germans remained outside their borders? Switzerland of course had (and has) a majority German populace, but then their neutrality in European affairs was by then already well-established. And then over in the west there was Alsace and Lorraine in France—controlled by the German Empire from 1871 to 1918. You’ll notice the Dutch and Flemish are marked in some Nazi maps as being “German” as well. But those borders were much more fixed than out east, where either Prussia or Austria had traditionally held large parts of those lands.

However, in eastern Europe, after the Munich Agreement, there were only pockets of scattered German populations now outside of Germany. Why would Hitler want to press any further in the east?

Shirer repeatedly points to Hitler’s views about Lebensraum expressed in Mein Kampf. There seems to be a pretty clear distinction between those contemporary observers who only listened to what Hitler said in his speeches and what he had expressed in his manifesto for Germany written a decade earlier. His speeches, and the corresponding propaganda machine run by Joseph Goebbels, flooded the zone with shit (to use a more contemporary phrase).

Shirer’s strategy in trying to size up the Nazis—a pretty useful one from my perspective—was to look at early writings and then to pay attention more to actions than to words. Given the incentive to lie and deceive and propagandize once in power, this seems like a useful approach: Distance yourself in some way from the propaganda machine. Keep track of concrete policy actions. Look at what motivated key people beforehand.

Beyond just Lebensraum, though, there was the territorial continuity of Germany. You can see that East Prussia centered around Königsberg (between Lithuania and Poland) is not connected to the rest of Germany, with the free city of Danzig and a good chunk of Germans living in that corridor that connected the two parts of Germany. It was to this area Hitler turned his attention first.

He began by having the Nazi Foreign Minister raising the question of Danzig in a more or less friendly way with the Polish ambassador. At first it seemed friendly, but the diplomacy quickly escalated.

Simultaneously, Hitler also secretly ordered his troops to prepare to take Danzig by force.

This was scarcely different from how Hitler had approached Austria or Czechoslovakia. However, because of how things had gone down since Munich, Prime Minister Chamberlain had shed his naive faith in Hitler’s good word. Suddenly, there was a difference. Foreign powers no longer had any reason to give Hitler the benefit of the doubt.

Increasingly skeptical of Nazi Germany, the British proposed on March 21, 1939, that the French and British actively engage to stop further aggression in Europe. On the same day, the Nazis didn’t just propose but demanded that the Danzig Corridor be turned over to Germany. From that day on, Europe went careening towards World War II.

As these diplomatic intrigues continued, Germany forced the Lithuanians to turn over the Memel strip (the small majority-German border area of Lithuania), which only put more pressure on neighboring Poland. Unlike Austria and Czechoslovakia, though, Poland resisted.

Then on March 31, Chamberlain addressed the House of Commons and swore that the French and British would lend all the support in their power” to defend Poland if it were attacked. Shirer notes how no one in Berlin seemed to take it seriously:

To anyone in Berlin that weekend when March 1939 came to an end, as this writer happened to be, the sudden British unilateral guarantee of Poland seemed incomprehensible.

Shirer goes on to note that Chamberlain had now “left to another nation the decision whether his country would go to war.”

Shirer himself then spent the first week of April 1939 in Poland trying to asssess whether the country was prepared militarily to resist the Nazis.

He determined:

that the Poles would not give in to Hitler’s threats, would fight if their land were invaded, but that militarily and politically they were in a disastrous position.

At this point, international leaders attempted to intervene in different ways to stop the impending war, notably President Roosevelt. On April 28, Hitler responded with a very long speech, which addressed every audience imaginable. In response to Roosevelt’s desire to settle issues “at the council table,” Hitler noted that the United States had rejected the Leauge of Nations, essentially calling out American hypocrisy.

And the hypocrisy Hitler highlighted didn’t stop there. He also pointed out that what Hitler was doing in eastern Europe was not that different from what the United States had done with the native Americans or what western European powers had done in their colonies. (The speech itself, with all the Western hypocrisies that Hitler very correctly highlights, is a Rorschach test about how you feel about the relationship between the Nazis and other western nations like the United Kingdom, France, and the United States—but that is a topic for another post…)

In the wake of this epic speech, Germany and Italy then signed the Pact of Steel, which committed the two countries to fight war and make peace together. Although, as we see in the last section, Italy was not 100% on board with the implications of this agreement since they really did not want to go to war in 1939.

Mussolini could not have been more different from Hitler. He wanted the glory of war but not the fighting. Hitler, on the other hand, betrayed no qualms about fighting.

At the same time that Italy and Germany were hashing out their issues in the middle of 1939, the Soviet Union suddenly became a major player. Both sides in the coming war began to entertain working with the hitherto pariah state. In essence, the Soviet Union became a global swing state. The French and English thought that Stalin could be a useful partner in containing Nazi Germany and defending the Poles. Hitler, recalling how Russia, Prussia, and Austria had partitioned Poland in the past, saw no reason not to do the same thing again. For Realpolitik reasons, he was suddenly willing to temporarily suppress his longtime anti-communist views.

In the next chapter, we’ll look at what came of this sudden—and unexpected—development.

My podcast interview with Professor Michael Socolow earlier this week was a lot of fun. I think you’ll enjoy the conversation as much as I did. Please check it out. The audio is free to all subscribers. And if you’re interested in supporting me for the time and material it takes to pull all of this together, you can upgrade to paid and get the full video version.

There should be another podcast this coming week with another great historian. So stay tuned!

As always let me know what you think.

Topical Posts

Podcast ep. 1: The Man, The Myth: Hitler in American Culture

The Problems with the German Character Explanation of the Nazis

Podcast ep. 2: Why are Dictators (and Techno-monarchs) Appealing?

Podcast ep. 3: Interview with a 20th Century War Correspondent: Jon Randal

If You’ve Fallen Behind on the Reading, This Post is For You

Who was William L. Shirer? — part 2 (The Nightmare Years 1934-1940)

Podcast ep. 4: The Exhilaration & Peril of Covering the Nazis (with Prof. Socolow)