And we're off!! — Rise and Fall of 3rd Reich Reading Group

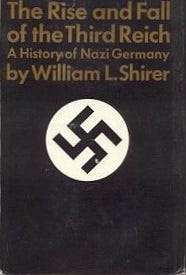

To launch our reading group of William L. Shirer's "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich", a few observations on the foreword

It’s January 20, 2025, and I’m very excited today to kick off our reading group of William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany! This week, we will be reading:

the Foreword

Chapter 1: Birth of the Third Reich

Chapter 2: Birth of the Nazi Party

In my edition, that’s just over 50 pages. For audio book types, that’s under three hours. (For full reading options and the entire calendar, please see the bottom of my first post here.)

For a 1250-page history, a foreword of only four pages comes across as remarkably concise.

In this short foreword, though, William Shirer covers a lot of ground. He explains why he decided to write the Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, justifies that decision, describes his sources, notes just how much he missed while covering the Nazis as a journalist, and then makes a world-historical pronouncement: because of the advent of the hydrogen bomb, Hitler is “the last of the great adventurer-conquerors.”

Sourcing a History of Nazi Germany

Shirer notes that although he lived and worked as a journalist in the Third Reich, he would not have written the book “had there not occurred at the end of World War II an event unique in history.”

What was that event?

The capture of most of the confidential archives of the German government and all its branches, including those of the Foreign Office, the Army and Navy, the National Socialist Party and Heinrich Himmler’s secret police.

Shirer then spends the majority of the foreword detailing those sources.

Now, one of the biggest differences that distinguishes a historian from a non-historian is the assessment of a list like this.

A historian spends hours and hours agonizing over sources. The majority of historical research is spent obtaining access to sources and then evaluating them. When you have had to scramble to find good sources or struggled to get access to sources that would balance out or complete your research, you have a much greater appreciation of just what this means. Sometimes there are simply no written sources at all. Occasionally, you know good sources exist, but, for any number of reasons, you can’t get access to them.

Consequently, there’s an element of empathy—shared pain—that emerges when a historian reads through someone else’s summary of their sources. There’s also some comparison going on: “Oh this is way more than what I did! Nice job.” And then, of course, a good dose of judgment: “I suppose this list of sources is actually sufficient to write this history…”

So allow me to say: Shirer’s list of sources in the foreword is astounding. As is the fact that they were all available in one place.

Why were they available? Well, the Nazis kept the records, for starters. And then they surrendered unconditionally. Allied troops made it to Berlin, the American troops recognized their importance and decided to preserve them.

This does not always happen.

Writing History vs. Writing Journalism

As a historian of journalism, another thing that stands out to me is the ways in which Shirer the journalist and Shirer the historian both contribute to making the book what it is.

Since the middle of the 20th century, it has become a commonplace that “journalism is the first draft of history.” If you want to capture the zeitgeist of a particular moment—whether as a historian, a late-night comedian, or the average Joe—the assumption is that you don’t have to look any further than a headline.

This is generally true, but not always. I’ve tried to push back against this assumption in my scholarly work.

In my dissertation, for instance, I used oral interviews with editors to reveal how the front page came together on days of world historical significance. Those moments are full of chance and contingency. There are disagreements among editors. And the truth isn’t always captured by the headline. Headline bait wasn’t born with the internet—catching eyeballs to sell the news has been part and parcel of the profession since the beginning.

It’s increasingly common to impugn the motives of journalists who are putting together this “first draft of history,” but the truth is that journalists—even with their all too human biases—are almost always doing their best in less than ideal conditions, against a merciless clock and with incomplete information.

Shirer the historian notes the limitations faced by Shirer the journalist:

It is quite remarkable how little those of us who were stationed in Germany during the Nazi time, journalists and diplomats, really knew of what was going on behind the facade of the Third Reich.

It is difficult for any journalist to acknowledge that he worked his tail off for almost a decade only to realize that he barely scraped the surface of what was actually happening. It is sobering to realize that you weren’t actually accomplishing your job as a journalist of conveying to the public what was happening on your beat. Shirer has the integrity to acknowledge this fact.

For me, this is one of the things that makes The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich so fascinating.

Shirer sat next to Hitler on stages before rallies. He watched the frenzied crowds up close. As he listened, he could compare the oratory of Mussolini and Hitler with William Jennings Bryan and Billy Sunday, having seen them all in person. He regularly had to evade Nazi censors. Close friends and colleagues were more than once seduced to join the dark side. His wife even struggled to get adequate medical attention after a C-section in 1938, because so many Jewish doctors and nurses were forced to flee. Most historians don’t have these kinds of experiences regarding the subject of their research.

But then, on the other hand, most journalists never move beyond those experiences to examine official documents and other sources after the fact. They never return to their old stories to reevaluate what they wrote.

In a difficult moment in his professional life, Shirer took a few years in the 1950s to dive into these sources and do just that. Shirer was not an academic historian but no Ivy Tower academic can begrudge him the title of historian. This is a real history. Shirer was both journalist and historian.

Shirer’s epic history of Nazi Germany combines the best of both roles. And, despite its flaws, this is why it still merits being read today.