A Historian's Take on a Journalist's History

Historian Richard J. Evans assesses William Shirer's "The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich"

William Shirer wrote the most famous book on Nazi Germany, but he is far from the only writer to take on the subject. I chose his book for a few reasons:

Even if long, it is a single volume.

Shirer was an eye-witness in Austria and Germany for many crucial events in the 1920s, 1930s, and early 1940s.

Shirer has a wonderful literary flair in his narration, which makes it enjoyable to read.

Shirer’s book is the best known history of Nazi Germany.

However, Shirer’s background as a journalist means that he didn’t do some of the work that many historians consider essential for the writing of history. I am proud of our book group and think this is the best starting point to learn about Nazi Germany, but, obviously, it is not the end of the story.

There are historians, better informed than me and than Shirer, who disagree with his perspective. And I think I owe it to the readers of this Substack to share with you some of this debate. Below you will find a long assessment of Shirer’s history by Richard J. Evans, an excellent historian.

Evans was Regius Professor of History at the University of Cambridge from 2008 until 2014. This was a few years before I matriculated at Cambridge. However, I got to know some of his former students, who appreciated him as a supervisor but were not always the most pleased that they had gotten caught up in controversies and department battles provoked by Evans’ prickly nature.

Personality aside, Evans is a phenomenal historian. The Regius Professor of History is one of the most prestigious chairs in History in all of the United Kingdom. It was founded by George I and requires a nomination by the Prime Minister. (As an aside, the current Regius Professor of History is Christopher Clark. A couple of my favorite memories at Cambridge involve conversations with Clark, where he engaged with me as if I were his equal…which I most assuredly am not.)

Returning to Evans—he was and is a social historian, which means that his focus is less on the great man version of history and more on how groups of people morph and change over time and why they are more likely to vote or act in a certain way over long periods of time. He was influenced by the Annales School, who preferred to look at social and economic factors rather than political or diplomatic ones.

Evans was a major figure in the 1980s Historikerstreit (“Historians’ dispute”), attacking certain conservative German historians that he (and others) felt whitewashed Germany’s past with what came across as apologies for Nazi Germany.

At the same time, Evans has also opposed the Sonderweg (“special path”) theory, which holds that Germany followed a particular path towards becoming a developed nation that virtually ensured that something along the lines of Nazi Germany would occur. Evans’ view is that other possibilities besides the Third Reich could have happened; they just didn’t.

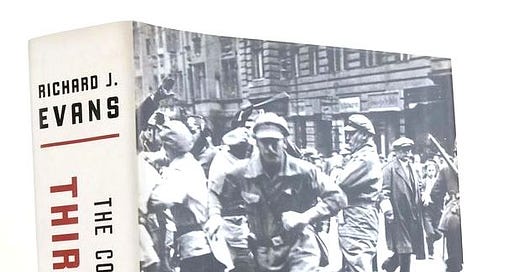

Between 2003 and 2008, Evans wrote a historical trilogy about Nazi Germany (The Coming of the Third Reich, The Third Reich In Power, and The Third Reich at War). I wanted to share with you Evans’ take on Shirer’s history, to give you a slightly more contrarian view of its value.

I quote it in its entirety, to give you a sense of how such a historian assesses the book we are all reading right now. On the second page of the Preface of the first book in the triology, The Coming of the Third Reich, Evans writes this about Shirer’s history of Nazi Germany.

The number of broad, general, large-scale histories of Nazi Germany that have been written for a general audience can be counted on the fingers of one hand. THe first of these, and by far the most successful, was William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, published in 1960. Shirer’s book has probably sold millions of copies in the four decades or more since its appearance. It has never gone out of print and remains the first port of call for many people who want a readable general history of Nazi Germany. There are good reasons for the book’s success. Shirer was an American journalist who reported from Nazi Germany until the United States entered the war in December, 1941, and he had a journalist’s eye for the telling detail and illuminating incident. His book is full of human interest, with many arresting quotations from the actors in the drama, and it is written with all the flair and style of a seasoned reporter’s despatches from the front. Yet it was universally panned by professional historians. The emigré German scholar Klaus Epstein spoke for many when he pointed out that Shirer’s book presented an ‘unbelievably crude’ account of Germany history, making it all seem to lead up inevitably to the Nazi seizure of power. It had ‘glaring gaps in its coverage. It concentrated far too much on high politics, foreign poilcy, and military events, and even in 1960 it was ‘in no way abreast of current scholarship dealing with the Nazi period’. Getting on for half a century later, this comment is even more justified than it was in Epstein’s day. For all its virtues, therefore, Shirer’s book cannot really deliver a history of Nazi Germany that meets the demands of the early twenty-first-century reader.

Evans, great historian that he is, makes a couple mistakes in this assessment. For one, Shirer did not leave Germany in December 1941, but rather a year earlier, when he learned that the Gestapo was building an espionage case against him. The first part of 1941, he worked on Berlin Diary, his observations that he couldn’t share as a broadcaster speaking from Berlin under the watch of Nazi censors. The book was published in June 1941, and he spent much of that year on a book tour in the United States for Berlin Diary.

Evans is also incorrect that Shirer’s book was “universally panned by professional historians.” Hugh Trevor-Roper, a historian at Oxford University, reviewed the book on October 16, 1960, for the New York Times Book Review, writing:

Now, as never before, the living witnesses can converge with the historical truth. All they need is a historian. In William L. Shirer they have found him. He was himself in Germany from 1935 to 1941—need one refer to his "Berlin Diary"? Since the war he has studied the massive documents made available by Hitler's total defeat. And now he has brought together his experience and his study in a monumental work, a documented, 1,200-page history of the whole episode of Hitler's Third Reich.

Of course, he will have some critics; every author has. I can think of points to criticize...

Then after listing a number of potential criticisms, Trevor-Roper concludes

…these are trivial criticisms in view of the greatness of his achievement. This is a splendid work of scholarship, objective in method, sound in judgment, inescapable in its conclusions."

Trevor-Roper, a professional historian, most assuredly did not “pan” Shirer’s book.

I tend to agree with Trevor-Roper: I think Shirer’s book is well worth reading. However, it is just a starting point. As Evans points out, our collective knowledge about the Third Reich has greatly expanded in the decades since 1945. There is always more to say, small ways to critique Shirer.

But he was there…and his book is pretty good, the best starting point.

Let me know what you think in the comments.

Some of you have contacted me privately to ask about Trevor-Roper's criticisms of Shirer.

Here they are, all raised in the form of questions:

Is he fair to Nietzsche and Gobineau?

Is he still so sure about the Reichstag fire?

Might he not have freed himself a little more from the day-to-day diplomacy fo 1938-39 to say more of the internal structure of Nazi Germany?

Might he not, in view of his own residence in Germany, have captured and conveyed a little more of the atmosphere of the time, portrayed the personalities, re-created the sense of permanent crisis in which Hitler kept the world?

Does Shirer even hint at Evan’s ‘working towards the fuhrer’ thesis, or is that something that is only developed by Evans or other historians later?